Let’s talk about reptiles and what makes them unique

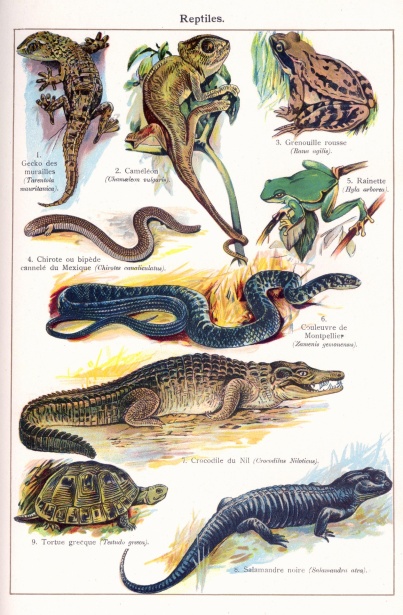

Lizards, dinosaurs, crocodiles, turtles, and snakes – all belong to that ancient and stout class of animals known as reptiles. This is a diverse group with more than 10,000 different species and a huge representation in the fossil record. Once the dominant land vertebrates on the planet, reptiles still occupy just about every single ecosystem outside of the extreme north and south.

The 8 characteristics of these interesting animals.

Rough scales – Reptile skin is covered in rough horny layers of scales, bony plates, or a combination of the two. These scales are composed of keratin, the same substance in nails, hair, and claws. The skin is actually rather thinner than you might suspect because it lacks the same dermal layer as mammals. But the watertight skin does allow the reptile to live and thrive in drier ecosystems.

Regular shedding – Reptiles shed their skin continuously throughout their lifetimes. Shedding tends to be the most frequent during the adolescent phase because the skin doesn’t actually grow in proportion with the body. The frequency of shedding tends to decrease once the reptile reaches adulthood. At that point, it’s mostly shed to maintain good health.

Cold-blooded – Reptiles have a naturally low metabolic rate, which helps to conserve energy but also means they lack any internal means to keep the body temperature consistent. Without fur or feathers for insulation, reptiles do not have the means to stay warm in cold temperatures. And without sweat glands, they also cannot remain cool in hot temperatures. To compensate, they rely on sunlight or shade as needed to alter their internal temperature. The leatherback sea turtle is the only reptile species with even some elements of warm-blooded physiology.

Egg-laying – With the exception of some snakes and lizards, which give birth to live young, all reptiles are oviparous and produce eggs in a nest. The soil temperature at this time determines whether the young are born male or female. Asexual reproduction is very rare, but it has been known to occur in some lizards and snakes.

Highly developed lungs – All reptiles rely on their lungs to breathe air. Even species with permeable skin and other adaptations never completely breathe without the use of their lungs.

Short digestive tracts – With a few exceptions, reptiles are meat eaters with relatively short digestive tracts. Due to their slower metabolism, they can afford to digest food slowly and consume a few meals. In its most extreme form, crocodiles, boas, and other reptiles can survive months on a single meal. Herbivorous reptiles do exist, but they face a problem: because they lack any complex dental system, they must swallow rocks and pebbles to grind up the plant matter in their digestive system, much like some bird species.

Chemoreception – Many but not all reptiles have chemically sensitive organs in the nose or the roof of the mouth for identifying prey. This ability supplements or even replaces the sense of smell. Snakes in particular sense chemicals in the air by flicking out their tongues rapidly. This has the effect of transferring odor particles from the tongue to the roof of the mouth.

Skull morphology – Several characteristics of the skull distinguish the reptile from other classes of animals. For instance, they have a single bone where the skull attaches to the first vertebrate, a single auditory bone – the stapes – that transmits vibrations from the eardrum to the inner ear and a very strong jaw. One of the interesting aspects of reptile morphology is that a few of these jawbones actually correspond to two earbones in mammals. It is believed that at some point in early mammalian evolution, these jaw bones moved to the back of the head and eventually formed the malleus and incus in the mammalian ear to assist with hearing higher-frequency sounds.

Exceptions to Oviparous Reproduction

As mentioned previously, the most dominant form of reptile reproduction is oviparous or egg-laying reproduction, but there are a few notable exceptions. Around 20% of all lizards and snakes, including the boas, do produce live young instead of eggs. These viviparous reptiles have a non-mammalian placenta or some other means through which nutrients are transferred from the mother to the offspring and vice versa for the waste. The main advantage of viviparous birth is that it protects the eggs from predators in a hostile environment. But this method of birth has a tradeoff since it’s taxing on the mother.

Only three reptile species, including the yellow-bellied three-toed skink of Australia, actually combine both eggs and live birthing methods (the rarity suggests that evolution probably does not favor this in-between stage). The skink’s offspring begins life encased in an egg, the same as any other reptile. But as the embryo develops, the egg begins to thin out until all that’s left upon its birth is a small membrane. The main problem with this method is that the thin egg shells don’t contain enough calcium to nourish the offspring. The mothers appear to compensate for this by secreting calcium from the uterus so it can be absorbed by the developing embryo. The evidence suggests that the skink can choose to lay eggs a few weeks early if it seems like there’s less danger to the offspring. In harsher climates, the mother will keep the offspring inside her body for longer to protect them.

Asexual reproduction is also quite rare, though more common than the egg-live birth method. Around 50 species of lizards and one species of snake partake in this method of reproduction. The evidence suggests that these reptiles may adopt an asexual lifestyle out of necessity – because they are genetically isolated from other groups. The problem with asexual reproduction is the lack of genetic variability: the offspring inherit the same susceptibility to diseases as the parent. But asexual reptiles appear to maintain genetic variation by beginning the reproductive process with twice the normal number of chromosomes.

The Four Orders of Reptiles.

The modern class of reptiles is generally divided into four different orders, each with its own distinct characteristics and morphologies.

Testudines – As the only order classified within the subclass Anapsida, Testudines is comprised of all known turtle species. Its main distinguishing characteristic is the hard cartilage-based shell that extends from the ribs and acts as a protective shield. The terms turtle, tortoise, and terrapin are based on regional dialects and do not represent any specific taxonomical or biological differences.

Squamata – The youngest order of reptiles also happens to be the most common. It is comprised of most reptile species, including all known lizards, snakes, geckos, and skinks. Many of the smallest reptiles in the world are classified as Squamata members. Venom is a common feature of at least some species in this order as a means to counter the defenses of their prey. Because the venom evolved from different pre-existing proteins throughout the body, the venoms are very diverse in form and function.

Crocodilia – This ancient order, which includes all modern alligators, crocodiles, caimans, and gharials, is one of the largest carnivorous predators on the planet. Featuring a flattened snout, tough skin, a long tail, and rows of large teeth, the Crocodilia species spend a great deal of their lives in or near water. This order is the closest living relative to the bird class. That’s because the Crocodilia ancestors were closely related to the dinosaurs.

Rhynchocephalia – This order dates all the way back to the Triassic Period some 200 to 250 million years ago. Once incredibly diverse, it has been reduced to only a single living genus, the lizard-like tuatara of New Zealand, which includes only two species. Despite the lizard-like appearance (they are a sister group of Squamata), this order actually shares some basic morphological traits in common with crocodiles and dinosaurs.